KEY TAKEAWAYS

- The West has an overly negative view on China’s future

- While there are a number of domestic economic challenges, China is moving up the value-added ladder

- The country is becoming increasingly competitive in many areas of technology and industry

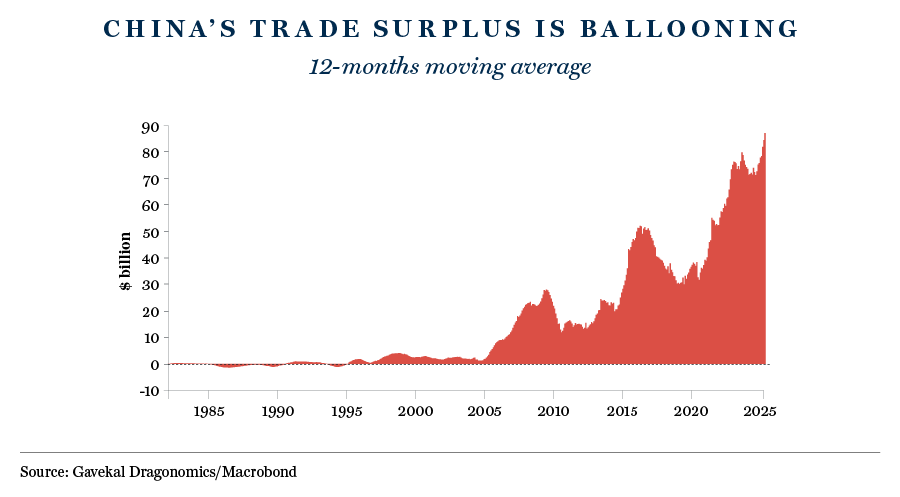

Viewed from the perspective of many in the West, the drip feed of negative commentary about China has been relentless in recent years. Yet the world’s second-largest economy still managed to grow at a 5% clip in 2024 while its massive trade surplus has continued to increase. Compounding concerns has been the recent escalation in trade hostilities between the US and China.

Among a number of voices proclaiming a bullish view on China is Louis-Vincent Gave, CEO of Gavekal, a financial research consultancy based in Hong Kong and Beijing. Louis, a former officer in the French army and investment banker, co-founded Gavekal in 1998. We have enjoyed regular conversations with Louis and his colleagues to hear their views and test our own thinking. I recently caught up with Louis to quiz him on his contrarian outlook.

Alan Lander: What’s behind your positive view on China’s prospects?

Louis-Vincent Gave: I think people’s views on China are massively skewed by how much time they’ve spent there. Their opinion that ‘China is circling the drain’ and is ‘uninvestable’ is arguably a function of the last time they were there, and that’s usually before the Covid-19 lockdowns and the Ukraine war. The economic transformation in the past five years has been massive, and it’s hitting our shores.

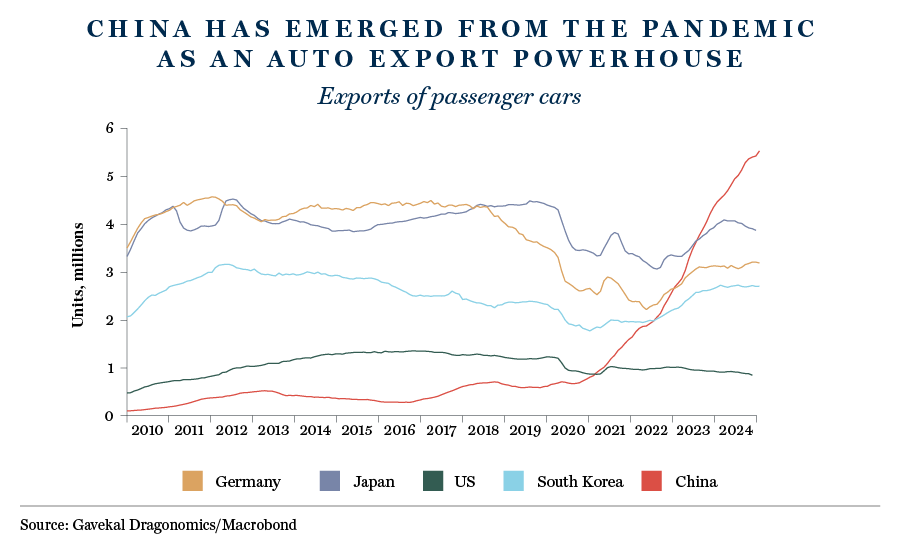

Today, China is the biggest exporter of automobiles and industrial robots in the world. It makes more solar panels than the rest of the world combined and is an exporter of nuclear power plants. China graduates more engineers than the rest of the world combined. The future is in China.

AL: But one of the concerns is that China is creating huge industrial overcapacity, so isn’t that a risk to its economy in the future?

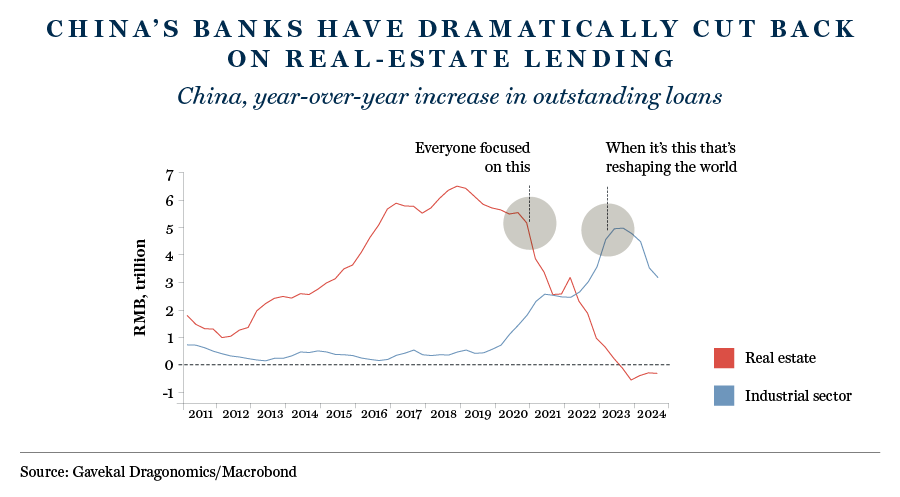

LVG: There is no doubt that overcapacity is being created, and this is deflationary. There will be winners and losers in each industry, which suggests an accumulation of bad loans. But this is the way Chinese capitalism works. It’s ultimately bad for the banks, but China maintains capital controls, so problems are internalised and it all gets funded through financial repression.

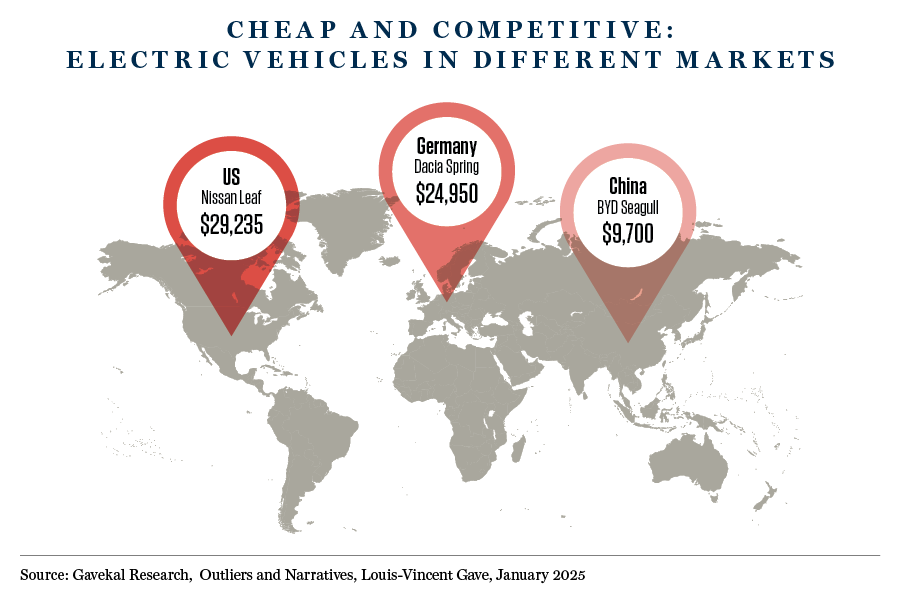

It’s a bit like The Hunger Games, where strong winners eventually emerge. Think of the quality, value and competitiveness of Chinese electric vehicles. And as Volkswagen can testify to, given its struggles with competition, these are global Hunger Games.

And the West has prompted this. The imposition of the semiconductor embargo by the US in 2018 triggered a move to self-sufficiency in every industrial sector. Rather like a French general fighting the Second World War by looking back at the First, the West missed the switch as commentators focused on the problems of the property market. The property-driven growth model was discarded with bank lending directed towards the building of advanced industries.

AL: In the context of ‘America First’ and growing fears in Europe that it’s being undermined by China, how will this dynamic of Chinese industrial competitiveness play out in a more protectionist world?

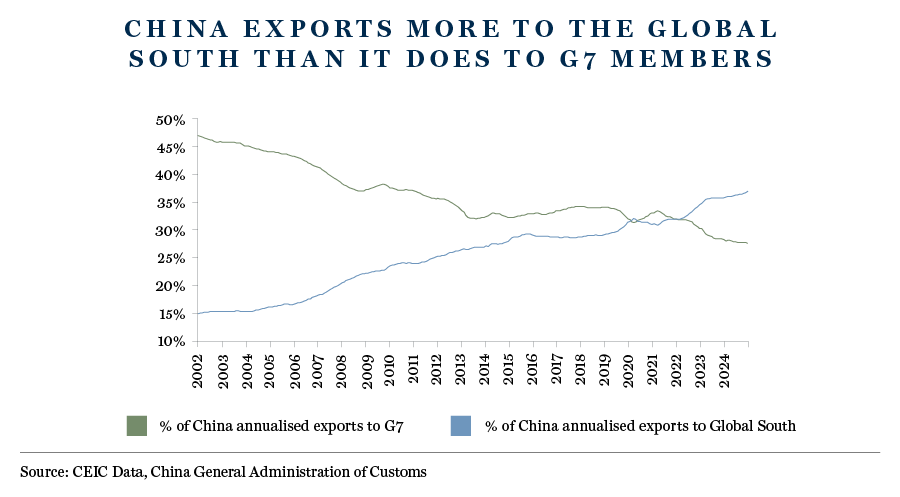

LVG: Firstly, there’s been a steady shift in trade that now sees the country exporting more to emerging markets than it does to developed countries, and these exports are growing very fast. Furthermore, these are high-value exports to EM countries – trains, power plants and automobiles – while increasingly the goods sold to developed markets are low value-added.

Regarding tariffs, think of the amount of consumer goods, such as iPhones, that are imported from China. It is Apple and/or the American consumer, not China, that will pay any tariffs. In the 2024 US election, the swing to the Republicans came from voters who earn less than $50,000 after a campaign that was fought over inflation, so President Trump’s ability to fight a long trade war that most Americans do not want may be limited.

The other point is that Apple has been trying for 10 years to source away from China, but is finding it extremely tough. This is true across many industries. Granted, that low-value products like Tupperware will not likely be made in China in the future, but China recognises that comparative advantages shift over time, hence the move up the value-added ladder.

More importantly, given the nature of the Chinese political system, the government can engage in economic dirigisme and ‘encourage’ some of the country’s top companies to invest in the US, which would dovetail well with President Trump’s invest in America strategy. This opens up a potential future path for a US-China compromise.

AL: China has accumulated a massive trade surplus, and a lot of cash is held overseas. Why isn’t it flowing back into the country? This would help the domestic economy, right?

LVG: Indeed, with that kind of trade surplus, this money should be repatriated. This would push up the exchange rate and perhaps support asset prices, which in turn would help hitherto subdued consumer spending. Instead, entrepreneurs have been buying gold, or sticking money in Hong Kong bank deposits. It’s symptomatic of a loss of confidence among businesses and, given uncertainty over the government’s interventionist policies in various sectors and concerns over tariffs, this is understandable. This lack of confidence is also evident in consumer behaviour, where the puncturing of the property market has dampened their spirits. It’s not about lack of money.

So now the government is focused on bolstering consumption. Hence the recent moves to stabilise the property market. Mortgage rates have been slashed and the monetary taps are firmly in the ‘on’ position.

AL: You often hear that China will suffer from Japanification, owing to demographic headwinds, a real estate bust and the associated deflation, with the prospect of its own ‘lost decade’ of growth looming large. What’s your view?

LVG: It’s different for a variety of reasons. Firstly, the sheer scale of the asset bubble in Japan was massive. There’s the famous statistic that at the peak of the bubble the land value of the Imperial Palace in Tokyo was greater than that of the whole of California. Real estate had impregnated everything, with the equity market valuing companies on the land they held. Secondly, Japan tightened fiscal policy to rein in the budget deficit. China is loosening it.

Thirdly, Japan became super-uncompetitive. It became so expensive in terms of prices and factors of production, not helped by a strong yen. China is cheap from many angles. The reason China enjoys such a huge trade balance is that it remains competitive in a way that Japan no longer was in the wake of the puncturing of its asset bubble.

Also, Japanese banks effectively went bust and stopped lending. Even zero interest rates didn’t alter their behaviour. This is not the case in China, where banks have government support and remain very accommodating.

We’re also in a different place in terms of their respective stock markets. In 1989, Japan was 45% of the MSCI World Index and it was 18% of global GDP. When it all went wrong, investors spent the next 15 years selling it. Now Japan is around 4% of global GDP and about 6% of the index.

By comparison, China is around 3% of the MSCI World Index and 17% of global GDP.

Nobody owns China.

This interview took place in January 2025 and featured in the Research Journal.

The views and opinions expressed in this article are those of the interviewee and do not necessarily reflect the position of Walter Scott.

Important Information

This article is provided for general information only and should not be construed as investment advice or a recommendation. This information does not represent and must not be construed as an offer or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell securities, commodities and/or any other financial instruments or products. This document may not be used for the purpose of an offer or solicitation in any jurisdiction or in any circumstances in which such an offer or solicitation is unlawful or not authorised.

Stock Examples

The information provided in this article relating to stock examples should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security. Any examples discussed are given in the context of the theme being explored.