Capturing the Opportunity Gareth Evans, Investment Analyst

The concept of carbon capture and storage has been around since the 1970s and most observers agree that it has a critical role to play in meeting the targets of the Paris agreement. So why is investment in this vitally important technology still lagging?

In 2018, the UN Framework Convention on Climate Change commissioned a special report from the Intergovernmental Panel on Climate Change to look at potential pathways to reaching the 2015 Paris agreement’s 1.5°C target. Of the four key scenarios modelled, all but one considered carbon capture and storage (CCS) as integral to success, while the remaining pathway relied on the unlikely scenario of a significant drop in energy demand in the developed world.

The concept of CCS was first developed in the 1970s. The technology involves capturing CO2 produced by large industrial plants, compressing it for transportation and then injecting it deep into a rock formation at a safe site, where it is permanently stored.

CARBON CAPTURE & STORAGE – THE PROCESS

The Unique Advantages of CCS

At present, CCS is the only technology in use that can both decarbonise irreplaceable industries with relatively high emissions, such as cement, iron and steel, and significantly reduce emissions from coal and gas power generation. While this is still a technology in its infancy, CCS is in commercial use and its benefits have already been demonstrated. Despite this, it is yet to be widely adopted at a commercial level. This is less to do with a lack of technical understanding than it is with a lack of investment and a consequent ability to derive economies of scale.

CCS is no different from most new technologies: it requires funding in its early ‘uneconomical’ stages to gain traction, while long-term success will ultimately depend on widespread adoption driving down costs and making it commercially viable. At present, that investment is not there. If CCS is to grow to play a meaningful role in mitigating global warming, then governments need to provide a level of investment similar to that enjoyed by renewables. The current gulf in support for the two is significant. In contrast to the $2.6trn of public funding committed to renewables, a mere $2bn of public funds had been spent on CCS by 2017.

More needs to be done

A Missed Opportunity?

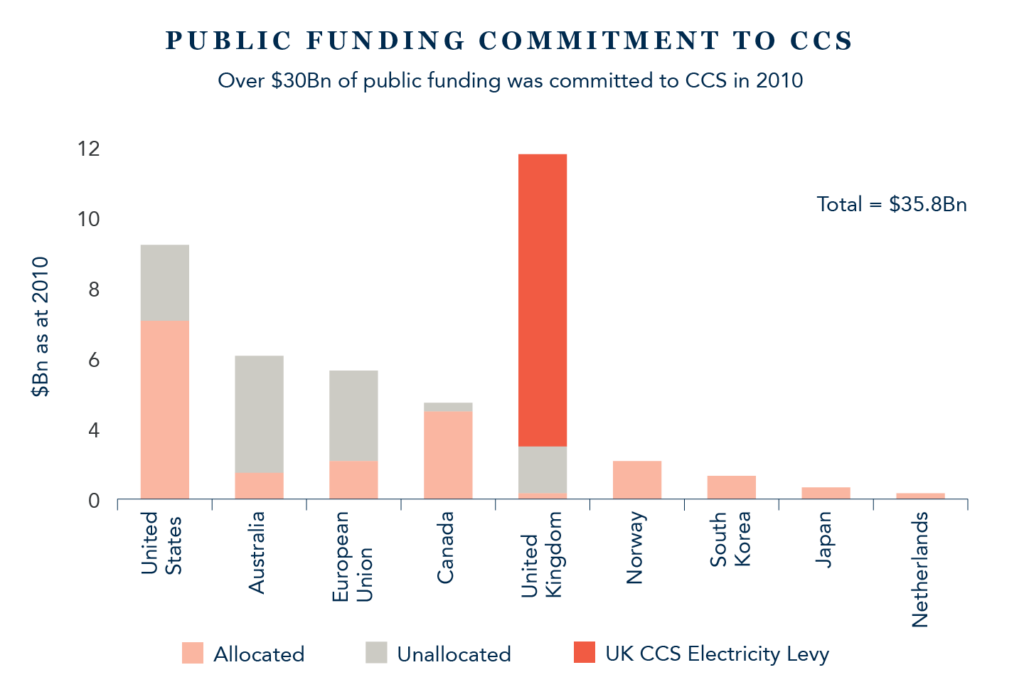

It was not supposed to be this way. In the early 2000s, there was considerable momentum behind CCS, and by 2010, cumulative public funding commitments totalled almost $36bn. However, as governments grappled with the fallout from the global financial crisis, projects were cancelled and funding withdrawn.

By 2020, according to the International Energy Agency, there were only around 25 large-scale CCS facilities operating or under construction globally, with a cumulative annual carbon capture of less than 50 million tonnes. When compared to the estimated ten billion tonnes of total CO2 emissions from coal-fired power plants alone in 2018, the inadequacy of the current CCS effort is clear.

The Future of CCS

It is self-evident that if CCS is to make the maximum contribution to emissions reductions, the pace of development and deployment needs to increase substantially from where it is today. A starting point in remedying this would be attributing a sufficient value to carbon in order to incentivise emissions reductions, perhaps in the form of a carbon tax or emissions-permit trading. Most modelling suggests that the adoption of CCS will only gain traction when carbon prices reach at least $25 per tonne. This is the level at which it crosses the current cost of mitigation. However, as we outline in more detail in our carbon pricing article, this is not where most carbon-pricing schemes are currently set. A 2020 World Bank report concluded that a $50-$100 per tonne carbon price would be required by 2030 in order to meet climate goals. Today, the price of the vast majority of emissions covered by a carbon-pricing scheme is below $10 per tonne.

There is evidence, however, that the need for action is beginning to sink in. In September 2020, the European Commission announced plans to target a 55% cut in greenhouse-gas emissions by 2030 as part of a broader European Green Deal programme. The commission warned that meeting this goal represents “a significant investment challenge” and said that investment in clean energy will have to increase by “around €350bn per year”. It is clear that CCS will have to be a prominent beneficiary of any such investment.

In Norway, meanwhile, the government has recently submitted a proposal to parliament to launch what it refers to as “the greatest climate project in Norwegian industry ever”. The €2.7bn Longship project will cover carbon capture, transportation and storage, and will help the country in its goal of achieving a 50-55% cut in domestic emissions by 2030, while also contributing to the creation of value chains for CCS in Europe. A step in the right direction, certainly, but as Norwegian Prime Minister Erna Solberg warned “for Longship to be a successful climate project for the future, other countries also have to start using this technology”.

From an investment perspective, we don’t view carbon capture and storage as a viable opportunity at this early point in its commercial development. Direct investment opportunities are still very much at the formative stage, with few of the characteristics – profitability, sustainable growth, resilience − we look for in companies. As further investment and wider commercial adoption drive down costs, this may change, but that will be a multi-year process if it does happen. For now, we are content to watch the development of CCS from the sidelines.

Important Information

This article is provided for general information purposes only. The information provided in this article relating to stock examples should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security. Any examples discussed are given in the context of the theme being explored. The opinions expressed in this article accurately reflect the views of Walter Scott at this date, and whilst opinions stated are honestly held, no reliance should be placed on them when making investment decisions.