The end of the (straight) line in manufacturing? Sasha Thompson, Investment Analyst

We have all lived in a world where we “take, make and waste” products. With ever-greater awareness of the flaws of this approach, there is now a determined shift away from this linear economic model towards a more circular economy.

The ambition for a circular economy is simple – the minimisation of waste through the design of more efficient products and the maximisation of value extracted from resources. This signals a departure from the linear take-make-waste model which assumes abundant resources that are easily sourced and subsequently cheaply discarded with few ramifications. Numerous data points suggest that the latter model is unsustainable. Reasons to strive for a more circular economy are wide-ranging, incorporating significant environmental and socioeconomic issues.

Eco-efficiency

Within the context of carbon neutrality, circularity is of paramount importance. The 2019 UN Global Resources Outlook report estimated that half of total global greenhouse-gas emissions are generated by the “extraction and processing of materials, fuels and food”1. As such, while alternative energy sources are crucial to meet the goals of the Paris agreement, the targets become considerably more difficult to achieve if we don’t change our production and consumption habits sufficiently to decouple GDP growth from global materials use. Other well-documented and pressing environmental issues related to the proliferating use of materials include the prevalence of plastics in our oceans, biodiversity loss and water scarcity.

In terms of socioeconomic benefits, McKinsey’s 2015 report entitled “Europe’s circular-economy opportunity” estimated that a transition to a more circular economy would generate €1.8trn of net economic benefit by 20302, while Cambridge Econometrics has suggested that it would create 700,000 high-skilled jobs3. These jobs would also likely be rooted in local communities, regenerating areas that have been left behind by the sweeping technological change of the 21st century. Reduced reliance on new materials would also allow governments and corporates to be more resilient to sudden resource price fluctuations that are frequently concentrated in a single geography.

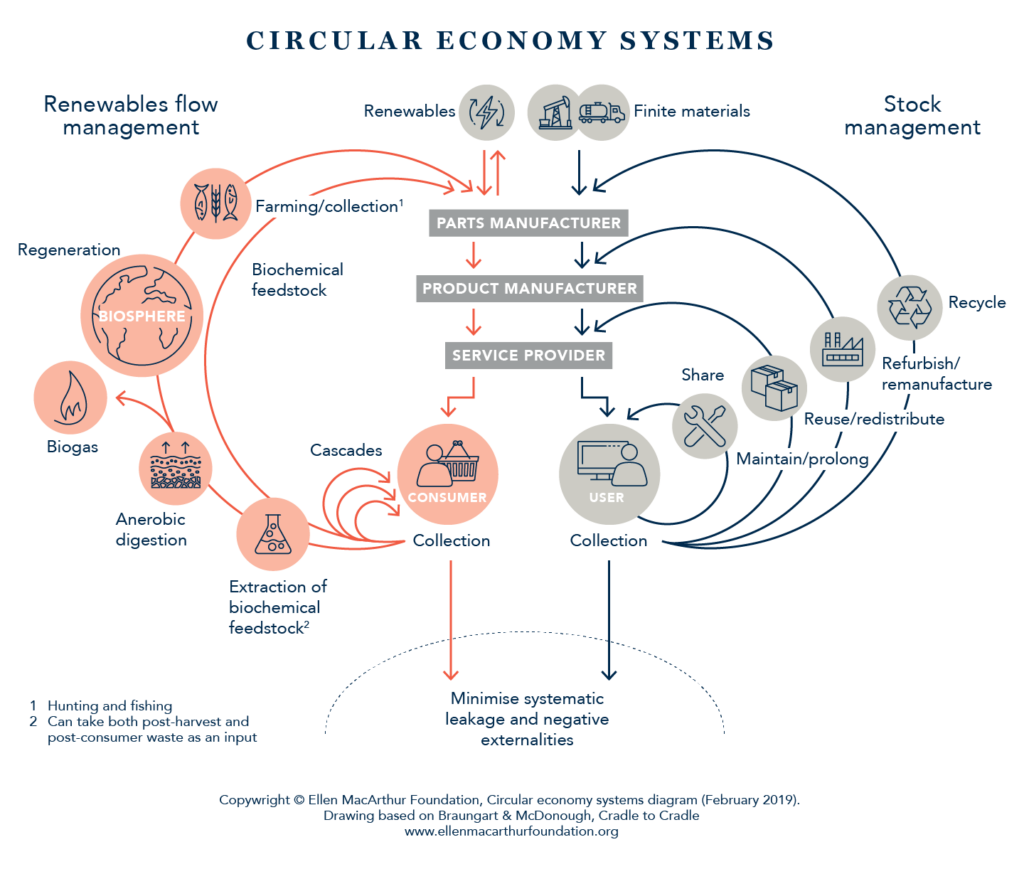

To achieve this, the circular economy envisages a system of mutually reinforcing cycles whereby materials are kept within supply chains for the maximum amount of time possible through the enhanced durability, reparability and upgradeability of products, and then either recycled or the maximum amount of valuable material extracted. Prior to this, waste can be significantly reduced at the design phase of a product alongside the use of sustainable substitutes.

It is also important to recognise that the circular economy is a vast umbrella under which various other models fall such as “the sharing economy”, “industrial symbiosis” and “the blue economy”. The below graphic from the Ellen MacArthur Foundation illustrates the cycles within the circular economy, highlighting the synthetic (blue) and natural (green) materials.

Leading the curve

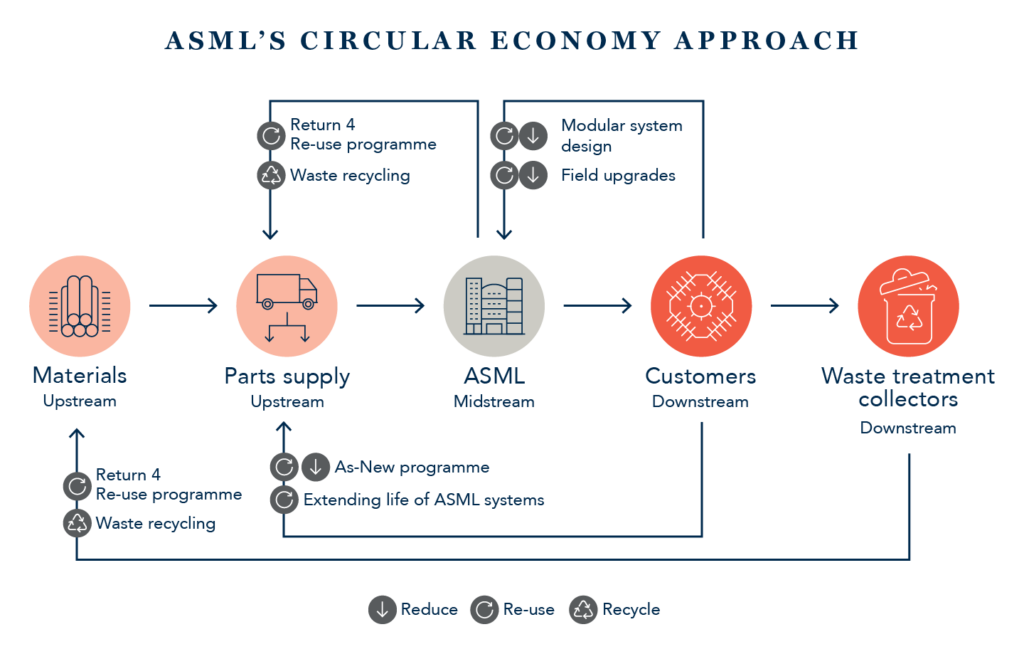

That all sounds good but how is it working in practice? As may be expected of an industry at the forefront of today’s technology, a number of companies within the semiconductor sector are pioneers in this transition to a circular economy. The semiconductor-component manufacturer ASML has taken substantial steps to realise its ambitions. Roughly 45% of its typical NXT system remains in place throughout numerous upgrade cycles. The company’s mature products and services business aims to refurbish and upgrade older lithography systems to extend their lifecycles, with 91% of total PAS systems ever sold still in use today, a testament to the company’s success and commitment to circular principles.

TSMC is another pioneer in this area, having introduced circular economy approaches to its business model in 2016. The semiconductor producer tracks unit waste disposal per wafer and has developed in-house capabilities to recycle electronic-grade sulphuric acid and to extract copper and cobalt from liquid waste with electroplating systems. Not only is this beneficial to the environment but it has allowed the company to be more self-sufficient, reducing its reliance on outsourcing the treatment of metal-containing liquid waste and on the purchase of industrial-grade sulphuric acid.

The top two global shoe brands are likewise embracing the circular economy. The Nike Grind initiative recovered approximately 87 million pounds of footwear scrap in 2019, which was then repurposed to create materials used in premium running tracks, basketball courts, and new shoes4. Another of the company’s circular initiatives is the Nike Adventure Club, a footwear subscription service for children whose styles and sizes change at an accelerated pace. Nike’s target for 2020 is to eliminate all footwear manufacturing waste sent to landfill or incineration.

Similarly, Adidas launched its Parley range in 2015 in collaboration with environmental organisation Parley for the Oceans. The range seeks to address the ocean plastic problem by incorporating collected waste material into the design of Adidas shoes. In 2020, Adidas made 15 million pairs of shoes made from Parley Ocean Plastic and is targeting 17 million for 20215. Other actions include the creation of a 100% fully recyclable shoe and a tennis dress that is fully biodegradable.

As one of the world’s largest and most influential companies, Alphabet described its goal to achieve “a circular Google” in a report by the same name in June 20196. According to its environmental reports, nearly one-fifth of newly deployed servers in 2017 were remanufactured units. The company resold over 3.5 million components into secondary markets in 2018, rather than sending them to landfill7. Data centres are particularly water intensive and Alphabet has devised creative uses for seawater in Finland and canal water in Belgium to increase the circularity of its operations. As for its consumer goods, the company hopes that 100% of its own-brand products will include substantial recycled materials by 2022. However, Alphabet doesn’t solely focus on its own operations, looking to partner with local authorities to fund landfill gas projects, provide grants to promising water-conservation solutions, and use its search and YouTube platforms to educate users about circularity.

These are just some examples of the breadth of circular solutions being adopted by companies across all industries. The circular economy is now a key part of the solution as we all strive for a more sustainable future and should no longer be considered a niche concept with limited application. It will be interesting to see how the regulatory landscape develops, with increasing calls to place circularity at the forefront of green agendas, including the use of tools such as carbon pricing to incentivise a transition away from take-make-waste models.

At Walter Scott, we have enhanced our analysis of companies’ sustainability claims with an appraisal of circularity, particularly with regard to the manufacturing, apparel and fast-moving consumer-goods industries. Thus far, through our discussions with management teams, we’ve been encouraged by what we have seen, but there is still certainly scope to do more.

- UN Environment Programme, Annual Report 2019, Letter from the Executive Director

- McKinsey & Company, Europe’s circular-economy opportunity

- European Commission, Impacts of circular economy policies on the labour market

- The CSR Journal, NIKE Global Impact and CSR Report – NIKE Spent $81.9 million on community development

- Adidas, In 2021, for the first time, more than 60 percent of all products will be made with sustainable materials

- Google, A Circular Google

- Google, Environmental Report 2019

Important Information

This article is provided for general information purposes only. The information provided in this article relating to stock examples should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security. Any examples discussed are given in the context of the theme being explored. The opinions expressed in this article accurately reflect the views of Walter Scott at this date, and whilst opinions stated are honestly held, no reliance should be placed on them when making investment decisions.