Why methane matters Callum Levon, Investment Assistant

Methane is well known for its warming effects but could the natural gas helpfully act as a bridge fuel in the transition from fossil fuels to renewables?

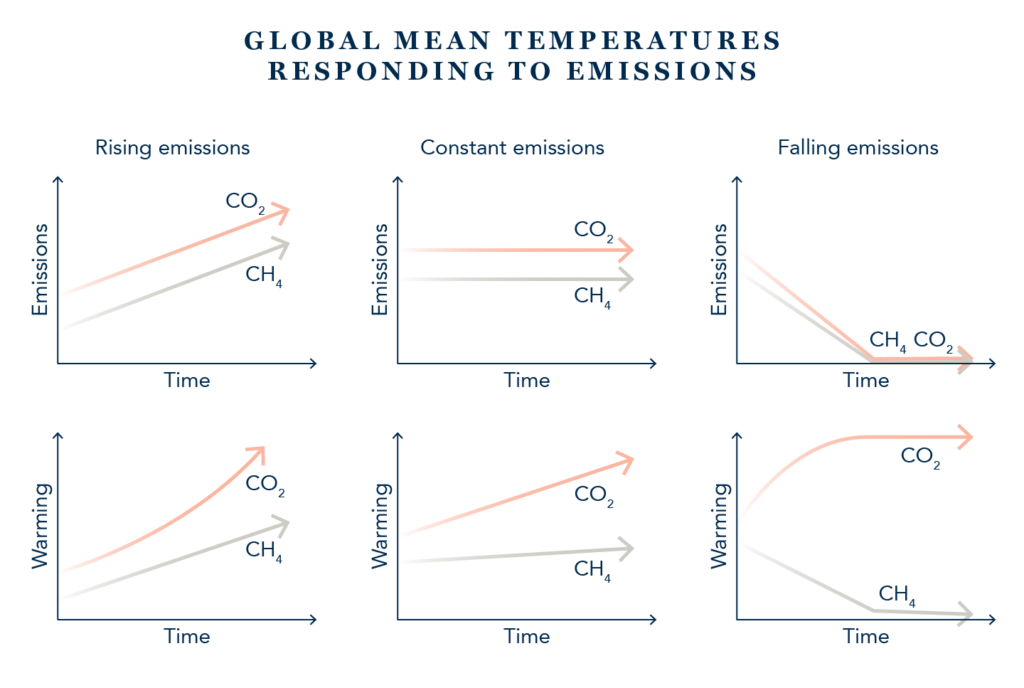

Methane is often crudely characterised by cows, or rather the gases which they emit. This simple imagery can often play down the significance of this natural gas. It is the second most important greenhouse gas, representing 35–50% of the global emissions budget. To put it into context, one tonne of methane has a warming effect of ~80 times more than one tonne of CO2 over a 20-year period, and ~28 times over a 100-year period. But, crucially, methane has a shorter atmospheric lifetime than CO21,2, meaning that it will remain in the air for just 12 years compared with centuries for the CO2. Even more significant is the difference in the way the two gases behave, as illustrated by the charts below.

For example, constant methane emissions equate to no warming effect, while constant CO2 emissions lead to a warming effect. It is aspects like this that cause problems for policy responses and conversations in the public sphere around methane.

To return to those cows, when considering carbon tax policy, we can look at the hypothetical example of a closed coal plant and a dairy farmer. The first would not currently be taxed due to the fact it is closed – however the warming effect of its operations will be felt for centuries. The second would currently be charged a carbon tax due to the cow’s methane emissions. However, if the dairy farm does not increase its herd, it will not contribute to global warming. In fact, if it reduces the size of its herd, that would actually contribute to cooling the earth. If governments’ aim is to tax behaviour they don’t like and subsidise those they do, this doesn’t quite fit.

This is a problem when we see reports that refer to ”CO2 equivalent” emissions (often relating to those cows again), as they crudely multiply methane emissions by ~28 or ~80, when comparing to a 100-year or 20-year time frame respectively, in order to make a comparison.

A good example of this was a recent Greenpeace report entitled “Farming for Failure”, where the environmental group found that CO2 equivalent emissions for the EU agriculture sector were roughly equal to EU transport emissions, inferring the unsustainability of meat consumption. Arguably, the key issue with this conclusion is that the majority of the EU’s agriculture emissions are methane3, leading to a sizeable overstatement of the warming effect of agriculture. Greenpeace is by no means a lone offender on this front but these types of reports do make it hard for civil society to determine how to most effectively allocate resources to combat climate change.

Total

As one of the oil majors at the forefront of the energy transition, Total is beginning to take its methane emissions seriously. The French company released 64,000 tonnes of methane in 2020, 98% of this was from its E&P operations, with the majority coming from venting and flaring. Interestingly, it reports fugitive emissions as a minority source. This could be interpreted as a positive in that Total can potentially control its methane emissions in the future with better management. It plans to decrease methane emissions through a variety of methods such as installing closed-flare systems and reducing its use of cold venting. The company also aims to reduce methane emissions by one quarter by 2025, compared to 2019 levels. Lastly, it is also introducing a dedicated R&D programme to tackle emissions. This includes a dedicated testing platform, airborne leak-detection system using drones, and a move towards continuous monitoring with satellites, cameras and micro sensors.

Methane’s role in a low-carbon future

Natural gas, which is predominantly methane, has long been touted as a potential “bridge fuel”, to help support the transition from fossil fuels to renewables. When combusted, pipeline gas emissions are 49% lower than coal, making gas an attractive option for the short term. However there is one crucial assumption – that the natural gas is wholly combusted. As we saw from the charts above, methane has a very high warming effect on the planet. So, what proportion of natural gas is not combusted, and what does it mean? A study by Stanford University suggests that natural gas leakage rates are likely to be between 2-4% percent of gas production. While an analysis of fracking sites by Cornell University found that 4-8% of the methane from shale-gas production escapes to the atmosphere over the lifetime of a well. Even after production has ceased, leaks can continue to be a problem. Researchers at Harvard University surveyed the literature on methane leaks and estimated that emissions from abandoned wells could total up to five million tonnes of methane per year. As we can see, it is difficult to pin down precise leakage rates. The takeaway is that oil and gas firms will need to double down on monitoring and leak prevention in order for gas to make a meaningful contribution to the energy transition.

A bridge too far?

How much leakage is too much? Making the assumption a near-zero carbon energy source is achieved in 30 years, the evidence suggests that if natural gas leaks reach 3% of production, then there are periods when it is a worse option than new more efficient coal plants. If leaks hit 6%, gas could be worse even than old inefficient coal plants. Given that we do not yet have official leakage figures, we do not know how close we are to these critical points. Nonetheless, the necessity of ameliorating leaks is abundantly clear.

Important as this is, coal and gas may be an ‘apples to oranges’ comparison. It’s all about time frames. Coal stations simply take a lot longer than gas ones to get up and running. With the transition to renewables on its way, and battery technology not yet adequate to run power grids on 100% renewable energy, we will need to offset issues of intermittency on those days when the sun doesn’t shine and the wind doesn’t blow. On those days, it will be gas peaker plants, which burn natural gas, that are the more obvious choice if supply isn’t meeting demand. In this sense, it could be the case that more renewables means more gas. Should this be the case, there are numerous opportunities and challenges within the gas space. The most notable opportunity might be increased demand for gas during the transition period. The greatest challenge for energy firms will be the increased scrutiny of efficiency and emissions.

Europe's Methane Strategy

Awareness that methane needs to be part of climate change policy is growing. As recently as October 2020, the European Commission released its strategy to reduce methane emissions.

The commission plans to partner with the UN to establish an independent international methane emissions observatory. The observatory will collect and publish anthropogenic methane emissions data at a global level. With this data, it plans to develop a Methane Supply Index to increase transparency in global methane emissions.

In the energy sector, the commission will deliver legislative proposals regarding compulsory measurement, reporting, and verification for all energy-related methane emissions, and an obligation to improve leak detection and repair of natural gas infrastructure. It will also consider legislation on eliminating routine venting and flaring. The commission is also considering introducing methane-emission-reduction targets and standards for fossil energy consumed and imported in the EU. This point is particularly important as the commission is seeking to shift the onus onto consumers rather than the emitters having sole responsibility.

In agriculture, the commission will assemble a group of experts to analyse life-cycle methane emissions. This will look at aspects such as livestock, manure and feed management, as well as how new technologies and practices can reduce emissions4.

Important Information

This article is provided for general information purposes only. The information provided in this article relating to stock examples should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security. Any examples discussed are given in the context of the theme being explored. The opinions expressed in this article accurately reflect the views of Walter Scott at this date, and whilst opinions stated are honestly held, no reliance should be placed on them when making investment decisions.