An increasingly difficult investment case Alex O’Neill, Investment Assistant

Nuclear is another area of the energy debate that starkly divides opinion, its advantages understandably obscured by tragic incidents. Yet it remains an important part of the global energy supply today. Looking longer term, the picture is more complex and, despite the many merits of nuclear energy, due to cost and regulation, it looks likely to be relegated from the league table of leading global energy sources.

After surging in the 1960s and 1970s, construction of nuclear reactors slowed dramatically in the 1980s and 1990s on the back of slower growth in energy demand, safety concerns and lower fossil-fuel costs. However, more recently, construction has picked up once again with 54 new reactors under construction today, 40 of which are in developing economies1. However, this investment does not, in our view, represent a renaissance in attitudes towards nuclear energy. Instead, it represents a fix to the world’s immediate energy needs. Longer term, as today’s investment in renewable energy bears fruit, bringing with it less complex and less costly energy supplies, nuclear looks likely to wane.

- Nuclear power accounted for ~10% of global electricity supply in 20182.

- In 2019, there were 452 nuclear power reactors in operation in 31 countries around the world.

- In advanced economies, nuclear power is the largest low-carbon source of electricity, providing 40% of all low-carbon generation3.

The case for new nuclear supply?

The construction of new reactors may have picked up but the investment case for any such construction is challenging at best. Costs are substantial, budget over-runs and delays are commonplace.

The capital intensity of nuclear projects means that the cost of capital strongly influences generation cost and competitiveness against alternative technologies. For a five-year construction period, a University of Chicago study showed that the interest payments during construction can be as much as 30% of overall expenditure4. Long lead times create huge uncertainty around whether a plant, once commissioned, will be able to generate an acceptable return on investment given it isn’t possible to forecast revenues with a high level of certainty. By way of example, cutting the average electricity price assumption by $10 per megawatt hour (MWh) in 2040 lowers the net present value of a nuclear project launched today by around $200m. In that context, it is not surprising that all but seven of the 54 nuclear power plants under construction around the world are operated by state-owned companies5. This position seems unlikely to change anytime soon. In the current policy and market environment, it is difficult to see any privately owned utility embarking on a new nuclear project in Europe or North America without strong government support to minimise the financial risks to investors.

With the case for construction challenging, yet with a need to ensure immediate supply, focus has turned to extending the life of existing facilities. Technological advances now allow plants to operate beyond their typical 40-year design life.

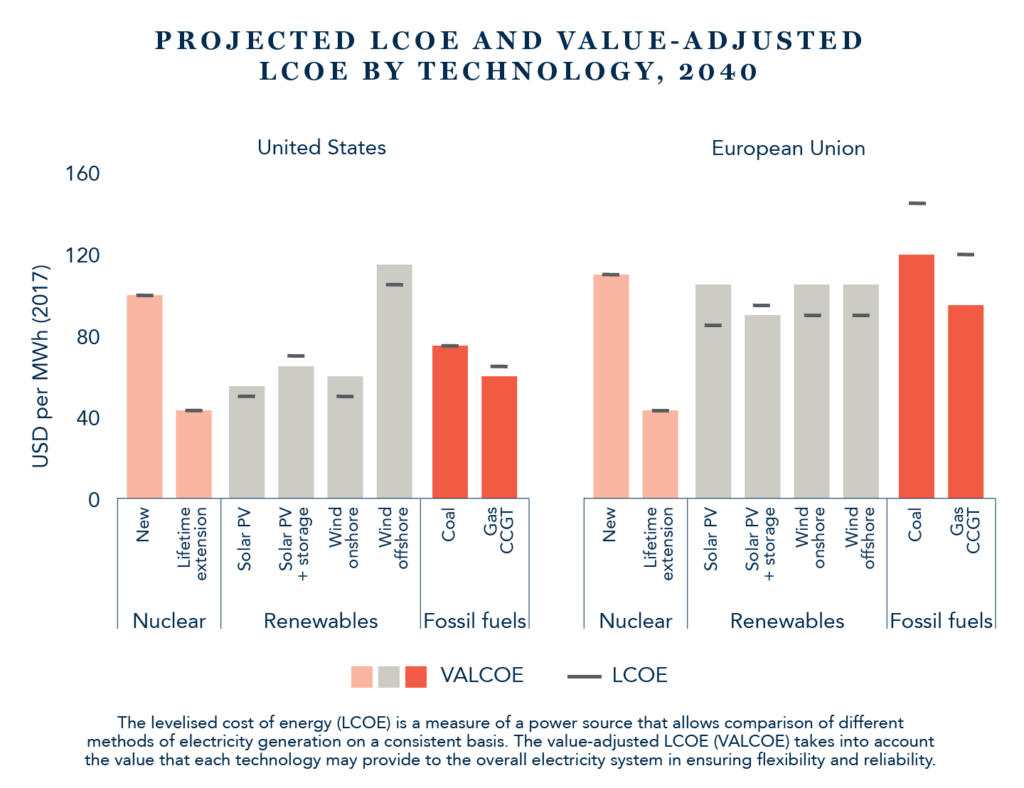

Outside of Japan and South Korea, around 90% of the nuclear reactors in advanced economies are more than 30 years’ old6. Lifetime extensions, therefore, represent one of the most cost-effective ways of providing low-carbon electricity today. The levelised cost of electricity (LCOE) associated with a nuclear lifetime extension generally falls in the range $40-60 per MWh. This compares to $50+ per MWh for new solar and wind projects under the same financing conditions today in the EU and US7.

Of course, whilst the numbers present a compelling case in providing a cost-effective source of electricity out to 2040, the case for lifetime extensions is not uniform and often complex. While nuclear operating costs are relatively low, plants require significant ongoing investments, not least robust safety upgrades to meet regulatory requirements.

The viability of such extensions is also undermined by depressed wholesale electricity prices. If these remain depressed in advanced economies – as a result of weak electricity demand, rapid growth in renewables-based power supply and in the US, low natural-gas prices – early plant retirements become more likely than extensions. Indeed, it is estimated that capacity in advanced economies will continue to decline as retirements gather pace, with around 25% of capacity set to be shut down by 20258.

Opportunities for long-term investors?

For equity investors, direct investment opportunities are limited and in any case the risk is probably outwith Walter Scott’s carefully judged tolerance. The case for the facilitating technologies that extend the working life of nuclear plants or reduce the carbon emissions is an uncertain one. Looking long term, we think it is likely that renewable investments will offer more opportunities that meet our criteria.

But the question of energy supply has infinite implications. In weighing up the environmental and social costs associated with energy production, nuclear could play an important role in the world’s transition away from fossil fuels. Whether it will or not depends as much on politics and public opinion as it does on finance. Although each country will likely take its own approach in trying to achieve a ‘clean energy’ transition, the ultimate goal is a universal one: establishing a secure, cost-effective and environmentally acceptable energy supply.

Important Information

This article is provided for general information purposes only. The information provided in this article relating to stock examples should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security. Any examples discussed are given in the context of the theme being explored. The opinions expressed in this article accurately reflect the views of Walter Scott at this date, and whilst opinions stated are honestly held, no reliance should be placed on them when making investment decisions.