Under the stewardship of President Joko Widodo, Indonesia, the largest economy in South-East Asia and fourth most-populous country in the world, is experiencing a sustained period of growth and stability. In September, investment manager Fraser Fox and investment analyst Michael Scott travelled to the country to dig a little deeper into this Asian success story.

It’s ten years since the Federal Reserve set hares running in financial markets by hinting that it might soon begin the process of scaling back its post-GFC asset purchase programme. Amidst the ensuing turmoil of the “taper tantrum” investors rushed to exit emerging market assets. One country at the sharp end of the upheaval was Indonesia, which alongside Brazil, India, Turkey and South Africa (the so-called “Fragile Five”) was considered particularly vulnerable to abrupt reversals in capital flows due to a large current account deficit and heavy reliance on external funding.

In the intervening years, however, Indonesia has undergone an impressive economic transformation, shedding its unwanted ‘fragile’ label in the process. Today, the largest economy in South-East Asia and fourth most-populous country in the world enjoys investment-grade status and is experiencing a sustained period of growth and stability. Of the world’s major economies, only India is projected to eclipse Indonesia for growth in 2024 and 2025.

Travel to Indonesia and it’s common to hear this economic turnaround attributed to the astute stewardship of Joko Widodo, the country’s long-serving president. Known colloquially as ‘Jokowi’, the former furniture salesman is credited with instigating a programme of infrastructure investment and regulatory reform that has helped to energise the Indonesian economy. Even more important have been measures aimed at unlocking the full potential of the country’s huge mineral reserves, particularly nickel.

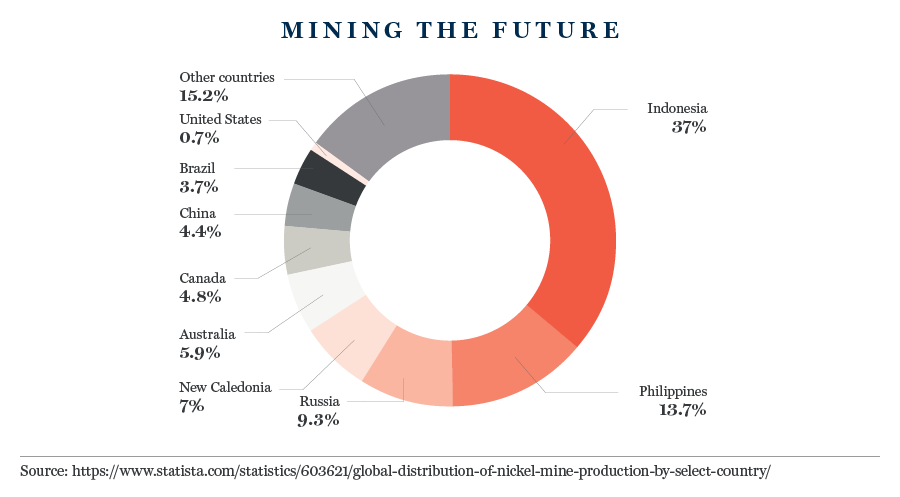

As the world’s largest nickel producer (see chart), Indonesia has benefited in recent decades from increased demand from China, and more recently from the electric-vehicle battery sector. However, it was Jokowi’s decision in 2020 to ban the export of nickel ore that turbo-charged revenues. By mandating that all nickel must be processed domestically, Indonesia has been able to attract greater foreign investment and capture more of the nickel value chain. By 2022, nickel-related revenues had reached an estimated US$30 billion, a more than ten-fold increase from 2013. Little wonder that Jokowi remains so popular with voters despite having been in power for almost ten years.

That popularity won’t be put to the electoral test again, however. Jokowi, who is constitutionally barred from serving a third term, will step down in 2024. But if there is any trepidation in corporate Indonesia as to who will follow in his footsteps, it wasn’t in evidence during the meetings we held with company management teams. Praise for Jokowi and his achievements was fulsome but business leaders appear to be looking beyond his tenure with a degree of confidence, reflective perhaps of the fact that two of the three candidates in the forthcoming election are current government ministers (one has picked Jokowi’s son as running mate, prompting allegations of nepotism). Policy continuity appears likely.

One plank of the Jokowi programme that looks almost certain to survive his departure is infrastructure investment. Inadequate infrastructure is a headwind to productivity anywhere but given the sheer dispersion of the Indonesian archipelago – some 17,000 islands spanning the equivalent of one-eight of the world’s circumference – the impact has been particularly acute. To address this, Jokowi established the National Strategic Projects initiative in 2016, pouring billions into long-term transport and energy works.

Business leaders seem to be looking beyond [Jokowi’s] tenure with a degree of confidence

Nowhere is the influence of this investment more evident than in the capital Jakarta, where the infamous traffic congestion is showing marked signs of improvement. The forthcoming completion of a 110 kilometre second ring road should further ease congestion and the economic damage that comes with it.

Whilst in Jakarta, we met with a company that’s been integral to the overhaul of the city’s transport network, Jasa Marga. As the dominant toll-road operator in Indonesia, Jasa Marga has a pipeline of projects that will keep it busy well into the next decade. With the second Jakarta ring road and a section of the Trans-Java toll road in the north of the island nearing completion, the business is turning its attention to the massive expansion of the highway network in south Java.

Of course, this is capital-intensive work carrying significant long-term execution risk. To compensate for this and to further encourage private investment, the Indonesian government has put in place a supportive industry structure. For Jasa Marga this includes multi-decade concessions (often up to fifty years), regular inflation-based tariff adjustments, and financial support for land acquisition and clearance. Combined with economically insensitive traffic volumes, these incentives ensure a good degree of certainty over future cash flows, with the last 20-to-25 years of a concession typically highly cash generative.

The investment case for Indonesia does not begin and end with infrastructure and minerals, however. Many of the structural trends underpinning the investment narrative for the wider South-East Asia region also apply: incomes are rising; the middle class is growing; and demographics are favourable. Furthermore, the relative under-penetration of markets and trends presents companies with significant growth opportunities.

The investment case for Indonesia does not begin and end with infrastructure and minerals

Avian Brands, for example, is the market leader in the Indonesian paint industry. Catering primarily to the professional painter – there is very little interest in DIY in Indonesia – Avian generates the bulk of its revenues from home renovations, a market with a strong tailwind from rising levels of prosperity.

Historically, Avian has grown faster than the wider paint market, a trend management believes will continue even as the market accelerates. Confidence is high too that the business can maintain its enviable gross margins, amongst the highest in the paint industry globally thanks to a vertically integrated business model and raw material sourcing from India and China. Longer term, the strategy is to consolidate the fragmented and still relatively immature Indonesian paint market.

Another play on rising household incomes is the convenience store operator Alfamart. The convenience model has grown rapidly over the last thirty years in Indonesia, but Alfamart’s management team sees plenty of scope for further expansion as increasingly prosperous customers shift from traditional to more modern retail formats. This is particularly true of those on low-to-middle incomes, Alfamart’s target customer.

Currently, there are 50,000 such stores across Indonesia, a penetration rate of one for a little over 5,000 people. Alfamart believes this will go to one for every 4,000 over time. Rising penetration alongside a growing population – Indonesia is projected to break the 300 million people barrier by 2030 – point to a durable growth runway for the retailer.

Indonesia is projected to break the 300 million people barrier by 2030

The same might be said for Indonesia as a whole. The stronger, more diversified and resilient Indonesian economy that has emerged in recent years is well-placed to enjoy a prolonged period of growth. From being very much a leveraged commodity play, there are now more strings to the Indonesian bow. Commodities will of course continue to be vitally important but the abundance of ‘new’ commodities – cobalt, nickel, copper – and a greater share of the value chain should serve to mitigate the impact of the inevitable cycles. Foreign direct investment, meanwhile, is booming and corporate confidence is high.

Returning from our trip, it was hard not to draw parallels with Indonesia’s situation and that of India, itself a former member of the Fragile Five. There too, a dominant political figure with an outsider’s backstory has embarked on an ambitious programme of modernisation, pushing through a series of reforms and ramping up infrastructure investment. Inevitably, given India’s scale, Narendra Modi receives more international attention than his Indonesian counterpart, but Jokowi’s impact within a domestic economic context has been no less pronounced. Many Indonesians and investors alike will be hoping his successor can deliver more of the same.

Further Insights

Video & Article: India Rising

Stock Examples

The information provided in this article relating to stock examples should not be considered a recommendation to buy or sell any particular security. Any examples discussed are given in the context of the theme being explored.

Important Information

This article is provided for general information only and should not be construed as investment advice or a recommendation. This information does not represent and must not be construed as an offer or a solicitation of an offer to buy or sell securities, commodities and/or any other financial instruments or products. This article may not be used for the purpose of an offer or solicitation in any jurisdiction or in any circumstances in which such an offer or solicitation is unlawful or not authorised.